I have been remiss in not doing these annual reviews more regularly. I have no excuse. Other words get in the way sometimes.

But this, one year into my “official” retirement, I have no excuse not to do. So.

I read, cover-to-cover, 89 books in 2022. Compared to 48 in 2021. I try to make it through 70 to 80 a year, but some years…well. A handful in ’21 were doorstops, but really, I have no excuse for not getting through the nearly 100 books I read only partly.

Of the 89 this past year, 40 were some species of science fiction. That’s up in percentage from the past few years. A handful were rereads, like Samuel R. Delany’s Tales of Neveryon, Heinlein’s Space Cadet, Laumer and Dickson’s Planet Run, Greg Bear’s Heads. As I’ve noted before, I rarely reread. I read slowly, compared to some, and I have too many books on my TBR pile to choose to go over something I’ve already been through. This past year, I’m finding that to be a mistake. (I started this a few years back with Charles Dickens. I’d read most of his work in high school, came away hating it, and deciding that I needed to revisit that impression. It has been…instructive.)

Planet Run by Keith Laumer and Gordon R. Dickson is an anomaly for me. It’s what a friend of mine calls a “shitkicker”—and adventure with not much else going for it but the adrenaline. A crusty old spacer is hauled out of retirement to participate in the planetary equivalent of the Oklahoma Land Rush. He’s seasoned, wizened, world-weary, but gets saddled with the wet-behind-the-ears son of the politician who has blackmailed him into doing this. Bad guys abound, betrayal happens, it would have made an excellent Bruce Willis film anytime in the past 20 years. I read it first at 13 and there is something about it that just does it for me. I’ve read it four or five times since and it is always fun. Nothing deep, nothing timeless (or maybe there is), nothing one couldn’t find in a good Zane Grey or Louis L’Amour (it is basically a western). But it still makes me smile. It is one of the few books I loved as a kid that does not make me cringe to read now.

The Bear…well, Greg Bear passed away November 19th, 2022, from complications from heart surgery. I still have a few unread Bear novels on my shelf, but I read his Queen of Angels for the first time and realized that there are 5 books in that universe, including Heads, which proved to be as wickedly clever this time as the first time. The jabs at Scientology are impossible to miss, but it’s not satire. Queen of Angels was fascinating and a book one wonders if it would be fêted today. It hues close to a few stereotypes that, while I felt he subverted, might nevertheless be read as problematic today. At its heart are questions of nurture vs nature psychology and the costs of potential intervention—therapy of a more intrusive type.

Of the SF read for the first time, then, right off the top was Gregory Benford’s Shadows of Eternity, which produced a curiously nostalgic reaction for me. Benford “borrowed” an alien species from Poul Anderson and wrote a very different sort of first contact novel that took me aesthetically right back to the Eighties, even as the approach to character and extrapolations of technology are very much of the moment.

I heartily recommend Stina Leicht’s Persephone Station, first in a series (?) that gives as an all-female crew (and supporting cast) in another “shitkicker” that has no lack of adrenaline and ample speculation involving corporations and indigenous rights and a neat Magnificent Seven riff.

Andy Weir’s Artemis could have come from an outline left behind by Heinlein. Enormous fun, set entirely on the moon, action, problem-solving, and—again—corporate shenanigans.

I read Ken McLeod’s trilogy beginning with Cosmonaut Keep, continuing with Dark Light and Engine City, which is a large-scale space opera somewhat in the mode of Iain M. Banks an involving interspecies intrigue, vast machinations, and ending on an ambivalent note where what problems have been plaguing the characters seem to be solved but not exactly resolved. He handles the whole time dilation question rather well and manages to tell family sagas and personal relationships against the background of centuries. (It’s tricky to do these kinds of sagas which center on families without it becoming A Family Saga, with all the kind of homey baking bread sentimentality one usually encounters.)

I want to make special note of Nicola Griffith’s Spear, which is a compact and compelling retelling of the Arthurian—or, rather, the Percival legend—done from an unexpected point of view. Firstly, the writing is, as we expect from Griffith, first-rate. Secondly, she delivers a feminist twist which is only that in retrospect. As always, the story comes first. But story and character are bound up in the double helix of narrative. Griffith is doing some of the best history-based fiction around. The sequel to Hild is coming out soon and we should be prepared for a treat.

Arkady Martine’s A Desolation Called Peace is the sequel to her marvelously complex debut, A Memory Called Empire. It picks up where the first left off and enriches the universe she has built, quite well. This is the kind of immersive world-building long-valued in SF/F, particularly effective because of the juxtaposition of cultures which throws the aspects of each into relief. Martine’s main character is herself something of an outsider, groping for Place in a milieu of which she has too little experience.

Another epic work in SF I think very important is Kim Stanley Robinson’s Ministry For The Future. This is in many ways not a science fiction novel—in fact, it could be argued that a good chunk of it is textbook—but it is speculative, in that none of the specific events detailed have happened but the world is very much ours. It presents a scenario in which the world finally tackles climate change. In that so many things work and come together to positive effect I suppose render the novel SF, but…

Becky Chambers’ new series, Monk and Robot, continues with A Prayer for the Crown Shy, part of the tor.com series of novellas. All I can say is that Chambers is one of my favorites authors. She writes about community is ways I find remarkable and refreshing in science fiction.

Two novels about radically altered futures I found compelling. Monica Byrne’s The Actual Star, which is reminiscent (in structure) of David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas, and Benjamin Rosenbaum’s The Unraveling. Both novels offer views of future social arrangements quite removed from our own and both present backgrounds of unexpected breadth. The writing in both is amazing and the ideas will linger.

To my great pleasure, John Crowley published a new one, Flint and Mirror, which indulges his penchant for presenting magic as a potential more than a reality and offering a view on the borderlands. This one is a historical, about the Irish Problem at the time of Elizabeth I. Unexpected.

I continued with Jacqueline Winspear’s Maisy Dobbs series. I haven’t decided yet whether she’s doing history with embedded mystery or the reverse, but the novels have been tracking Miss Dobbs chronologically as the world heads for WWII. The last two so far, war is upon Britain and Maisy finds herself doing more security work than private investigation. We have grown up with these people now, so to speak, and the world Winspear is investigating is marvelously evoked.

Not intending to, really, but I did a partial reread of the Ian Fleming James Bond novels. I indulged in a marathon review of the movies and wrote commentary and decided some comparison to the original novels and stories was in order. I was surprised both by how well-written many of them were and at the same time how shallow. I recall as a teenager plowing through them with relish. This time it was an academic review that yielded a few surprises, but on the whole I came away feeling I never have to look at them again.

I read Emily St. John Mandel’s new one, Sea of Tranquility. Whatever she might say, this is straight up science fiction, with time travel and an apparent time paradox. Given another fifty pages, she might have made it a very good SF novel. As it stands, it was enjoyable but derivative and relied too much on the good will of the reader. It was reminiscent of several older works by SF writers, most especially Poul Anderson’s Time Patrol stories. My best guess is, her point is to suggest that we all live in closed loops. (She might try to remember next time that gravity is different in other places and that someone who grew up on the moon might have a very difficult time standing up on Earth. Such details, which may seem fussy to literary writers, can make or break a narrative in science fiction.)

I finally read a Paul J. McAuley trilogy I had been meaning to for years, starting with Child of the River. In many ways it reminded of Gene Wolfe’s magisterial Book of the New Sun. Out in the hinterlands of galactic space, an artificial world with a long history that has evolved into a mythic background and a kind of avatar of a past race come to fulfill, etc etc. The adventures and worldbuilding are exceptional, but it ended with the feeling that another book would have been in order to satisfactorily wrap things up.

One last SF recommendation is Annalee Newitz’s new one, Terraformers, which draws on her strengths in anthropology and ecology and tells the story of the denizens of a world that has been remade by a corporation intending to lease it out to rich vacationers. The beings who did the actual work, however, presumably designed to die off when their utility is at an end, are still there and a struggle begins to claim rights. High finance, environmentalism, indigenous issues, and all the related politics combine in a rich, fascinating novel of generational evolution.

I’ve been dipping back into the past and catching up, filling in gaps. A couple of Clifford Simak novels, a reread of Ian Wallace’s Croyd (which is remarkably weird), early Le Guin (Rocannon’s World and Planet of Exile), and….

David Copperfield. Yes, the Dickens. I read this one aloud to my partner and came away with a modified view of Dickens. At least in this novel, what to a modern sensibilty comes across as verbosity, is actually very careful scene-setting and social explication. The 19th Century did not offer movies and the stage was not universally available. I found very little that might be excised from the narrative. It all mattered.

I read Piers Brendon’s The Dark Valley, which is a heavy history of the 1930s, from the onset of the Depression to the start of World War II. Brendon takes a global view and examines each major political aspect—America, Europe, Britain, Asia—and gives a narrative of the runaway cart that took the globe to war. The parallels to the present are clear, but also deceptive. Yes, there are movements and conditions, but the failure of solutions then should not be taken as inevitabilities now.

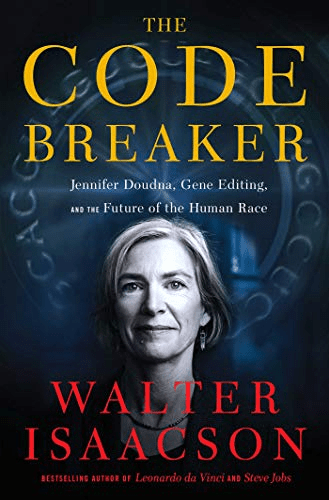

I read Walter Isaacson’s Code Breaker, the biography/history of Jennifer Doudna, the geneticist who has given us CRISPR and whose work was part of the technological foundation thst produce the COVID vaccine is apparently record time. Isaacson, as usual, does an excellent job of making the science accessible. The people, though, shine in this lucid view of modern science.

As is my usual habit, I read some odd bits of history. For my writing, I rarely do project-specific research. Instead, I cast a wide net and gather a variety of details until suddenly they become useful. To that end, I read the following: The Future of the Past by Alexander Stille; There Are Places In The World Where Rules Are Less Important Than Kindness by Carlo Rovelli; Utopia Drive by Erik Reece; Freethinkers and Strange Gods by Susan Jacoby; A Short History of Nearly Everything by Bill Bryson; Worldly Goods by Lisa Jardine; Beyond Measure by James Vincent.

And the rather impressive History of Philosophy by A.C. Grayling.

I can recommend all of the above whole-heartedly.

I also read Sherlockian novels that surprised me. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar (yes, him, the former basketball player) is a serious Sherlockian and did two novels centered on Mycroft. I recommend them. Sherlock is in them, of course, but not yet out of university. They are surprisingly good. Or perhaps not so surprising, Maybe the word is uniquely good. There have been pastiches and homages to Holmes and most of them are forgettable if enjoyable. These two I feel contribute meaningfully to the mythos.

Along those lines, the Victorian Age has become almost a genre in itself, and I read my first Langdon St. Ives book by James Blaylock. I’m still unsure what to make of it, but I was impressed. We shall see if I continue the series.

There are a number I have left out. Not that they were bad, but I’m not sure what to say about them here. I discovered some new-to-me authors that I recommend—Sarah Gailey, Daniel Marcus, Nadia Afifi.

I finally read a classic I had long avoided. High Wind In Jamaica by Richard Hughes. I’m still trying to decide how I feel about it. In many ways it is an ugly story. Children captured by pirates, who turn out to be quite not what anyone would expect. It seems to me to be a study of what happens when childhood fantasy collides with the fantasized reality. In that way, it is well done and evocative. What it says about human nature and the condition of childhood is complex and layered.

I may have further thoughts later. For now, this review has gone on long enough.

I’m looking forward yo 2023.

Good reading to you all.