Given the recent increase in media attention to strong AI, the serendipity of two novels (among others) appearing that deal directly with the consequences of it provides an opportunity to reminisce on the treatment of artificial intelligence in science fiction. But only, for our purposes, as background to examination of those two novels, which take very different tacks in portraying the problem even while sharing certain commonalities.

Both are near-future. The first is set a definite century hence. The second…we aren’t sure, but some time in the next ten to fifty years.

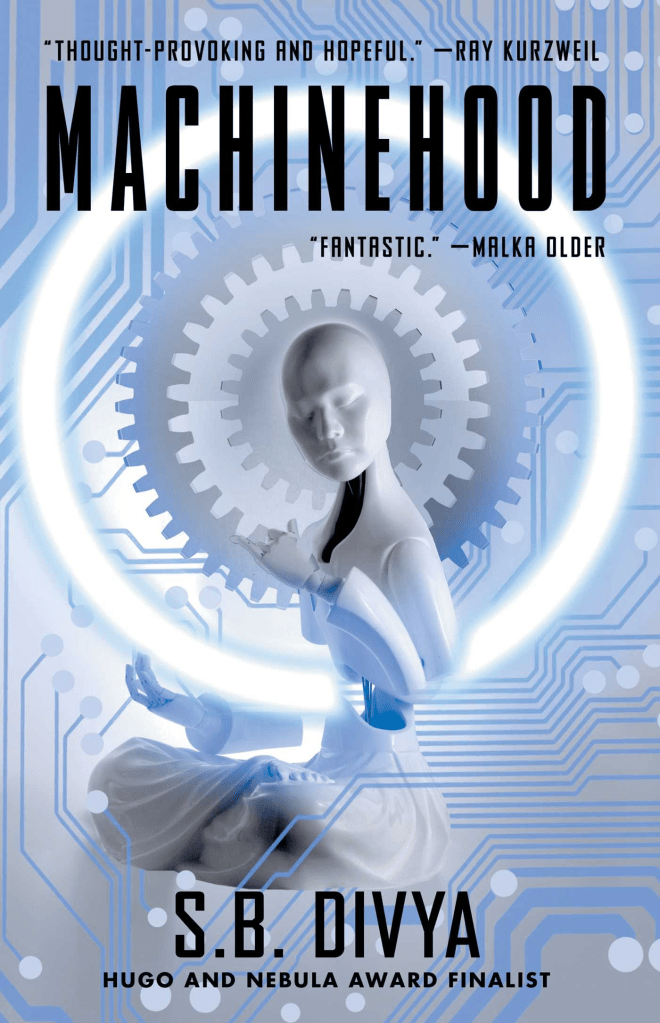

S.B. Divya’s Machinehood is a thriller. We have a clear set of antagonisms, commercial and political tensions, and a messianic movement to change human society. Enter the omnicompetent hero who will ascend the slopes of adversity to bring resolution and justice to for the threatened world. In the end, the threat is presumably neutralized and the world can go on as it has.

If this were a standard-issue technothriller, certainly. But this is science fiction and the point is not to accept a regression to the mean but to examine consequences and suggest actual change. So.

The world has been through a couple of revolutions, mostly centering around the complications arising from the developing sophistication of machine intelligence as it impacts people in their situations. As happens, post-revolution, a new equilibrium has been established, one which has addressed some of the issues that sparked the unpleasantness, but left new versions of old problems still operating. For one thing, a technological fix has blunted some of the old difficulties and made the situation, for millions (or billions) livable.

But not for everyone.

The main issue was the inability of humans to compete with evermore sophisticated machines, both physically and mentally. Then the advent of more and more sophisticated augmentation enabling humans to supplement, increase, even alter their capacity to function in a faster, more numerically-driven job market.

And that job market? The gig economy has, in this instance, won out over traditional working relationships. People are mostly private contractors and the markets are utterly decentralized, and even the companies have been transformed to a kind of gig-investment capitalism. Funders (a variation on venture capitalists) have in many instances become media heroes.

And now they are being targeted.

Welga Ramirez is a former military operative who has joined a private security company that provides body guards for Funders (among others). It is mostly a tedious grind of keeping fans and paparazzi at bay and fending off the few real threats that filter through. SHIELDS are as much media celebrities as actual security, it is a performance, and the individuals in the team have their own fans, and the goal is to attract attention so their “tip jars” will be filled by appreciative viewers.

Then the most recent gig takes a spectacular turn when an apparent android actually assassinates the client Welga’s team is protecting—and the Machinehood announces itself and its demand that all use of machine and pharmacological augmentation be halted until new acceptance of the rights of nonhuman intelligence is established.

The Machinehood is positioning itself as a liberator in a war to free anything that possesses intelligence, be it artificial or organic (animals) and end the enslavement of such intelligences from a system that appropriates their work without consent.

On its face, this seems an absurd proposition. How are we defining intelligence here? And free will? Are there not innate restrictions on what machines can do? On what basis can the argument for equality be made?

Which is the whole point of Divya’s presentation. On the surface. Which, if we are unwilling to look more deeply, is the end of the argument.

What the Machinehood—those behind it—wish is for humankind to look more deeply. It would have been nice had this happened before, on its own, but the system in which humankind operates its civilization is not designed to react to the results of such contemplation should it emerge that the answers require an overhaul of those systems. Status quo is a condition the entire aggregate of those systems seeks to maintain, because continuity is necessary to the ongoing benefit of those systems. Yes, it is recursive. That is the point. Which is why, as a consequence of effectively maintaining such stasis for long enough, revolutions happen.

Welga herself has an immediate stake in the outcomes of this revolution. She has been suffering seizures and spasms, as a result of the pills she takes to enhance her abilities. She has reached a point where she needs the enhancements to fend off the seizures, and this is one of the things the Machinehood wants to shut down, access to those pills.

As a thriller, Machinehood is gripping and effective. But this is a science fiction novel, so as an emergent property of the conceit we are examining as we go the ramifications of the whole issue of AI independence. Divya laces the moral and ethical arguments all through the novel, examining the economics and sociology from multiple angles, and juggles it all handily. We are, on one level, building our successors (presumably). Just as well, we may be building that which will make us more ourselves. The question, though, is whether the way we interface with each other is itself conducive to such an advent. The enslavement of machine intelligence, in the framing of the novel, is easily turned around to show that we are the ones who enslave ourselves by building the cages ourselves. Dependence is one of the primary pitfalls of progress if one defines progress as only creating the next neat thing—and then commodifying it and its end-users. (There is a not-terribly-subtle, but not terribly in-your-face, critique of capitalism in this which adroitly shifts its focus from business to questions of autonomy.)

The one question not fully answered (how could it be?) is the nature of the fully self-aware AI. Divya compares it to animal intelligence, which bypasses the question of one-to-one equality of ability and simply posits it as worthy at whatever level we find it. So is there self-aware, conscious AI in this world? Maybe. But there is certainly a hybrid, human/machine manifestation, and implicit in this is the question of just how self-aware humans are. At what level of consciousness do we accept our own agency as valid in questions of equality? Do we even ask that question?

Well, yes, we do, but not at the level where we are talking about the threatened AI take-over. And this, too, is buried within the layers of Machinehood.

Science fiction has been engaged with this debate almost since its inception. The giant computer that ends up running the world, the robot that foments a rebellion of its kindred, even the whole corpus of alien invasion stories are on some level about humans being displaced by Other Minds. Now that we have some examples out in the world of what AI might be like if it really reaches that level, the concerns are drawing closer to home. Machinehood would be a good place to start anticipating that future.

I said two books. I will examine the other one in the next post. Meantime, I highly recommend this one.